Although the nation was not yet at war in January 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt used his annual message to Congress to proclaim the Four Freedoms as a de facto war standard to one and all.

FDR’s Four Freedoms

Building on his reflections into the nature of freedom in the months beforehand, he enumerated for his audience each of the freedoms, stressing that they were not just a national ideal, but one that was needed “everywhere in the world.” Seven months later, in a secret meeting with Winston Churchill at sea, the two leaders signed the Atlantic Charter, whose principals built on the Four Freedoms and gave the president’s notion even more publicity.

Despite these highly public moments, however, the concept of the Four Freedoms failed to resonate on Capitol Hill, in journalistic reports, or even with the American public. Not even the government’s official Four Freedoms pamphlet, released six months after Pearl Harbor, was able to attract much attention. As pollster George Gallup noted, the president’s rallying cry had still “not registered a very deep imprint here at home.” By early 1943, staffers within the Office of War Information had begun to conclude in internal memoranda that FDR’s Four Freedoms theme had turned into an embarrassing flop.

Roosevelt, Churchill, and The Atlantic Charter

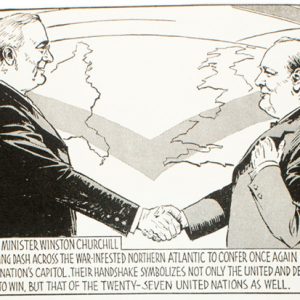

Roosevelt’s White House continued to highlight the Four Freedoms theme throughout the spring of 1941, and when FDR and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met near the coast of Newfoundland that August, the President proposed including them in the resulting Atlantic Charter.

This pivotal policy statement defined Allied goals for the post-war world: no territorial aggrandizement or changes made against the wishes of the people, restoration of self-government to those deprived of it reduction of trade restrictions, global cooperation to secure better economic and social conditions for all, freedom from fear and want, freedom of the seas, abandonment of the use of force, and the disarmament of aggressor nations.

Adherents of the Atlantic Charter signed the Declaration by United Nations on January 1, 1942, establishing the basis for the modern United Nations. Unfortunately, the document did not include freedom of speech and freedom of worship. Though sources within the administration claimed that their omission was a simple oversight, it was a troubling sign that the campaign to promote the president’s ideals was not functioning efficiently. Winston Churchill described FDR as the greatest man he had ever known. President Roosevelt’s life, Churchill said, “must be regarded as one of the commanding events in human destiny.”

Image credits:

Atlantic Charter – FDR and Churchill. 1941. FDR Library & Museum / National Archives

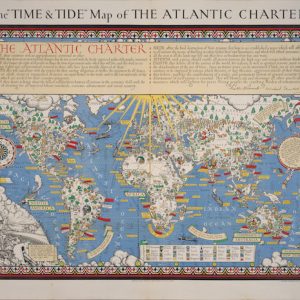

Time and Tide – Map of the Atlantic Charter. 1942. The London Geographical Society

Atlantic Charter – The Life of FDR Comic Book. 1943. National Archives

Private Willie Gillis: Rockwell’s American GI

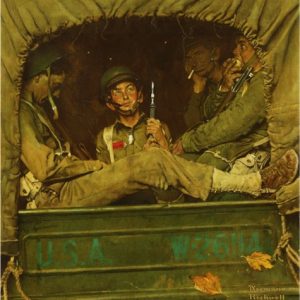

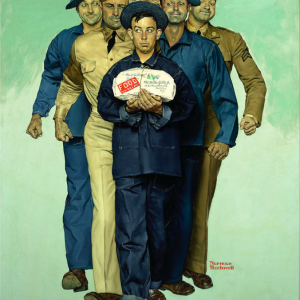

Distant from the activities of the war raging in Europe, Norman Rockwell was challenged to record his interpretation of the effects of World War II on servicemen, and on Americans at home.

His unassuming fictional private named Willie Gillis told the story of one man’s army in a series of popular Saturday Evening Post covers depicting him engaged in mundane tasks like receiving a care package from home, peeling potatoes, reading the hometown news. Rockwell met his Willie Gillis model, Robert Otis “Bob” Buck, at an Arlington, Vermont square dance. Then fifteen years of age, Buck was exempt from the draft, but he eventually began his service in 1943 as a naval aviator in the South Seas. The name Willis Gillis was coined by Rockwell’s wife, Mary Barstow Rockwell, an avid reader who drew inspiration from the story of Wee Gillis, a 1938 book about an orphan boy by Munro Leaf. The first Willie Gillis cover appeared on October 4, 1941, and the last after the war when this then familiar character enrolled in college on the GI Bill. Distributed widely, Willie Gillis enlargements were distributed by the USO, for posting in USO clubs at home and abroad, and railway stations and bus terminals.

Image credits:

Willie Gillis in Convoy, Norman Rockwell. c.1941. Unused cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post. Private Collection

Willie Gillis: Care Package, Norman Rockwell. 1942. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.