President Roosevelt made clear that the Four Freedoms were “no vision of a distant millennium.” Their odyssey did not end with FDR, nor with Rockwell. As World War II came to a close, the Allies began to hold planning meetings for what would become the United Nations.

Freedom’s Legacy

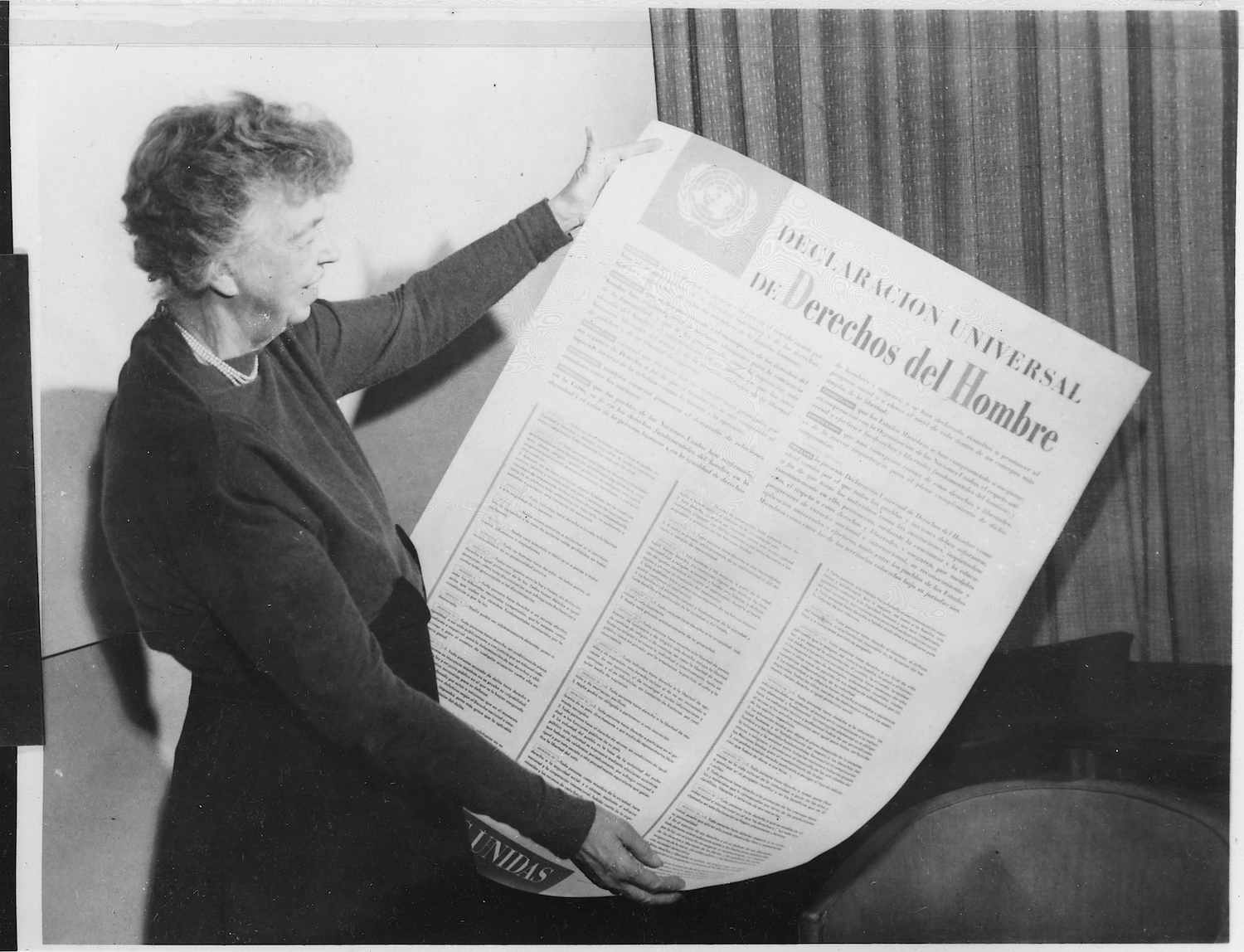

Eleanor Roosevelt, who championed the late president’s legacy, ceaselessly touted FDR’s freedoms as an appropriate summation of democracy and human rights, and war weary nations agreed. Enshrined in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Four Freedoms are a testament and an inspiration that arose from the ashes of war to affirm the precious nature of freedom everywhere in the world.

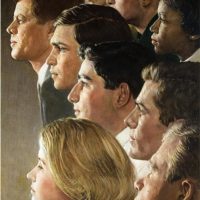

The Four Freedoms have continued to play a prominent role in national and international thought. Many constitutions have adopted these ideals as a guarantee of human rights. Heroic individuals—from those who have fought for the rights of enslaved populations to those who have dared to criticize totalitarian governments—have been recipients of the Roosevelt Institute’s Four Freedoms Awards. The Four Freedoms Park, a memorial to FDR on New York’s Roosevelt Island, is a reminder of the challenge that we continue to face in upholding freedom at home and abroad.

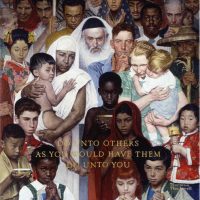

Rockwell’s interpretations, too, have lived on. His Four Freedoms are among the most recognizable images in American history. Whether we encounter them in the original, in print, or online, they are constant reminders of the profound influence of visual imagery on the human imagination. They reveal FDR’s timeless ideals in real world terms, even as they remind us that we, too, are heirs to these cherished values.

Eleanor Roosevelt and the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights

Just as Franklin D. Roosevelt envisioned the Four Freedoms that Norman Rockwell immortalized on canvas, Eleanor Roosevelt inspired the citizens and leaders of the world to acknowledge their continued significance.

Convinced that the United States had been “spared for a purpose” from the destruction the war had inflicted on other nations, she seized all avenues at her disposal—speeches, newspaper columns, articles, private conversation, correspondence—to urge Americans to recognize what was a stake and assume both the responsibility and the financial cost of world leadership. Fervently and repeatedly, Roosevelt cautioned her fellow Americans: “You cannot live for yourselves alone. You depend on the rest of the world and the rest of the world depends on you.” She understood how crucial a commonly shared vision could be in overcoming the haunting legacy of war.

Established in 1946 by the UN General Assembly, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights promptly elected Roosevelt its chair. Charged with creating an international bill of rights, the UNCHR put forward, for the first time, a definitive outline of the fundamental human rights to be universally protected. To accomplish this, Roosevelt conducted more than three thousand hours of debate, and had to create a climate in which all eighteen member nations—which represented very different political and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world—could envision and articulate rights and freedoms. The Declaration was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris, on December 10, 1948. Since then, it has inspired dozens of international covenants, the creation of international courts, new governments, and an increasingly powerful international movement. She considered this work to be her finest achievement, as it instituted a legacy for the Four Freedoms and left them in our hands to protect.

Changing Times: Rockwell and Civil Rights

In the 1960’s, leaving behind his beloved storytelling scenes, Norman Rockwell threw himself into a new genre—the documentation of social issues.

As evidenced in his Freedoms paintings, he wanted to make a difference with his art, and as a trusted and highly marketable illustrator, he had the opportunity to do so. Humor and pathos—traits that made his Saturday Evening Post covers successful—were replaced by the direct, reportorial style of magazine editorials.

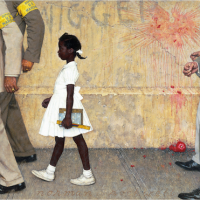

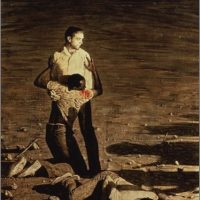

After ending his forty-seven year career with The Post in 1963, Rockwell sought new artistic challenges. His first assignment for Look—The Problem We All Live With—portrayed a six-year-old African-American girl being escorted by U.S. marshals to her first day at an all-white school in New Orleans, an assertion on moral decency. In 1965, Rockwell focused on the murder of three civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and in 1967, he chose children, once again, to illustrate desegregation in our nation’s suburbs. In an interview later in his life, Rockwell recalled that he once had to paint out an African-American person in a picture since The Post’s policy dictated showing people of color in service industry jobs only. Freed from such restraints, Rockwell anxiously sought opportunities to correct the editorial prejudices reflected in his previous work.

Image Credits:

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), The Problem We All Live With, 1963. Illustration for

Look, January 14, 1964. Collection of Norman Rockwell Museum.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), Murder in Mississippi, 1965. Collection of Norman Rockwell

Museum. ©Norman Rockwell Family Agency. All rights reserved.

The Four Freedoms Today

Today, the Four Freedoms are celebrated in various ways. One of the most notable is with the Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park. It is the first memorial dedicated to the former President in his home state of New York. Located on the southern tip of Roosevelt Island in New York City, it is the last work of the late Louis I. Kahn, an iconic architect of the 20th century. The Park celebrates the Four Freedoms, as pronounced in President Roosevelt’s famous January 6, 1941 State of the Union speech.

Image Credit:

Photo by B. Koch, Four Freedoms Park Conservancy