In the spring of 1942, Norman Rockwell was working on a piece commissioned by the Ordnance Department of the US Army, a painting of a machine gunner in need of ammunition.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms

Posters featuring Let’s Give Him Enough and On Time were distributed to munitions factories throughout the country to encourage production. But Rockwell wanted to do more for the war effort and determined to illustrate Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms. Finding new ideas for paintings never came easily, but this was a greater challenge.

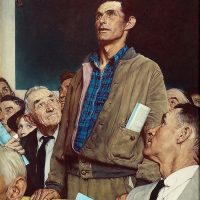

While considering his options, Rockwell by chance attended a town meeting where a Vermont neighbor was met with respect when he rose among his neighbors to voice an unpopular view. That night he awoke with the realization that he could best paint the Four Freedoms from the perspective of his own experiences, using everyday scenes as his guide. Rockwell made some sketches and, accompanied by fellow Saturday Evening Post artist Mead Schaeffer, went to Washington to propose his ideas.

The timing was wrong—the Ordnance Department did not have the resources for another commission. Disappointed, Rockwell stopped at Curtis Publishing Company in Philadelphia on his way home and presented his concept to Post editor Ben Hibbs. Hibbs immediately made plans to publish the illustrations, giving Rockwell permission to interrupt his cover work for a period of three months. He “got a bad case of stage fright,” though, and it was more than two months before he even began the project. “It was so darned high-blown,” Rockwell said. “Somehow I just couldn’t get my mind around it.” Despite his early misgivings, the paintings were a phenomenal success. After their publication, the magazine received thousands of requests for reprints, and in May 1943, the Post and the US Department of the Treasury announced a joint campaign to sell war bonds and stamps capitalizing on Rockwell’s vision.

Image credits:

Freedom of Speech, Norman Rockwell. 1943. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.

Freedom of Worship, Norman Rockwell. 1943. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.

Freedom from Want, Norman Rockwell. 1943. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.

Freedom from Fear, Norman Rockwell. 1943. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.

Norman Rockwell’s Creative Process

In the summer of 1942, when he was contemplating the Four Freedoms, Norman Rockwell was at the peak of his career and one of the most famous imagemakers in America. Though he struggled for months with how Roosevelt’s ideas could most effectively be portrayed, he resolved to root the universal, symbolic images in his own experiences and surroundings, using his Arlington, Vermont neighbors as models.

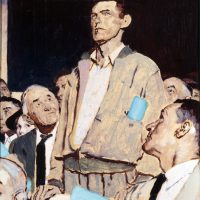

As was his complex, customary process, the artist’s thumbnail drawings and large scale charcoal sketches, no longer extant, were followed by preliminary color studies in oil before he finished his paintings seven months later. Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear were clearly conceptualized in his mind from the start, but Freedom of Speech and Freedom of Worship presented greater challenges. For each painting, he carefully choreographed the expressions and poses of each of his chosen models, and worked closely with his studio assistant Gene Pelham to photograph them for future reference. Freedom of Worship was initially set in a barber shop with people of different faiths and races chatting amiably and waiting their turn, a notion that Rockwell ultimately rejected as stereotypical. For Freedom of Speech, he experimented with several different vantage points, including two that engulfed the speaker in the crowd. In the final work, the speaker stands heads and shoulders above the observers, the clear center of attention. Fortunately, Rockwell’s Four Freedoms escaped destruction in a fire that destroyed his Arlington, Vermont studio shortly after they were delivered to The Saturday Evening Post. His reference photographs and most related artworks did not survive the blaze.

Image credits:

Annual Report – Arlington, VT – 1941, 1941.

Freedom of Speech (study), Norman Rockwell. 1942.

Freedom of Speech (sketch), Norman Rockwell. 1942. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.

Freedom of Worship (study), Norman Rockwell. 1942.

The Four Freedoms War Bond Show

In April 1943, one month after their appearance in the Saturday Evening Post, Rockwell’s original paintings began a sixteen-city Four Freedoms War Bond Show tour to publicize the Second War Loan Drive. The U.S. Treasury Department, realizing their potential to generate revenue through the sale of war bonds and to boost public morale, partnered with the Post to sponsor the tour.

Starting in Washington, DC, and gradually working its way around to points west, the exhibition featured hundreds of other artworks, posters, pamphlets, and manuscripts. Each stop vied to offer the biggest thrills and the most notable celebrity appearances, and volunteers were at the ready to would sell war bonds to an avid public. At the Boston stop, local organizers brought in the original models from Rockwell’s paintings. In Buffalo, visitors purchased enough war bonds to sponsor four new fighter-bombers, each named after one of the Freedoms. Portland, Oregon, used “over 1,000 column inches of newspaper publicity” to attract more than one hundred thousand bond purchasers to that city’s stop on the tour. From June 16 to 26, 1943, the exhibition was on view at New York’s Rockefeller Center, and overall, became the rallying point of a massive national outpouring of patriotic enthusiasm.

Rockwell himself ended up being part of the tour, but only for the first stop. He appeared at Hecht’s department store in downtown Washington, DC, but found that he had no appetite for the nonstop routine of signing autographs, meeting celebrities, and talking to reporters. Asked to continue with the exhibition, Rockwell allowed the protective Post editor Ben Hibbs to say, “No, Norman’s going to stay home and do Post covers.” Despite that, the tour did extremely well, raising $132 million in war bond sales and reached 1.2 million war-weary viewers. As important was the elevation of Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms in the public consciousness, and their embrace as democratic ideals worth fighting for.

Image credits:

Norman Rockwell Signing War Bonds Posters, 1943. Norman Rockwell Museum Collection. © Norman Rockwell Family Agency