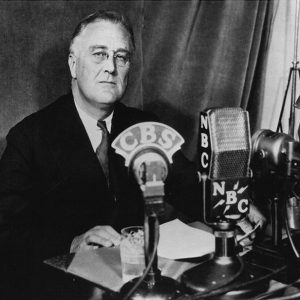

President Franklin D. Roosevelt famously told Americans in 1933 that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” but the nation was justified in its concerns during that turbulent time.

The War Generation

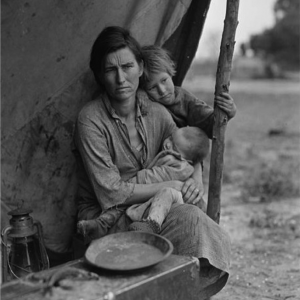

The stock market crash of 1929 had swiftly transformed the Roaring Twenties into the Great Depression. Banks closed their doors, bread lines became a common sight, and so-called Hoovervilles dotted the landscape. Jim Crow policies and racial inequality were facts of life for millions, and much of the nation’s grain belt became a dusty wasteland, fostering a mass exodus of destitute migrants seeking jobs that were no longer available. Dorothea Lange’s timeless photograph of a forlorn pea picker and her daughters came to represent a generation and a nation that seemed to have lost its way.

The President and his New Deal team worked intensively to address the emergency, but they were simultaneously becoming concerned about the international situation. As they were well aware, much of the world shared in America’s economic misery, and by the mid-1930s a number of aggressive dictators in Europe and Asia who addressed the global malaise by offering a kind of new fascism had begun to emerge. Americans were overwhelmingly isolationist at the time, and concerned about solving their domestic problems first. FDR had to be content with speaking out against international lawlessness, yet as the end of the decade neared, he also began to muse about the meaning of freedom on a worldwide scale.

Photo credits:

FDR’s first inauguration speech, 1933. FDR Library & Museum / National Archives

Family listening to radio, c. 1938. National Archives

FDR giving fireside chat, c. 1938. FDR Library & Museum / National Archives

“The only thing we have to fear, is fear itself.” Franklin D. Roosevelt

The Great Depression

The longest and most severe economic downturn of the twentieth century, the Great Depression began on Black Tuesday with the stock market crash of October 29, 1929, and lasted for a decade.

Though it originated in the United States, it prompted deflation and unemployment in almost every country in the world. Nationally, this represented the harshest adversity faced by Americans since the Civil War. By 1933, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office, a quarter of the labor force was without work, wages had fallen dramatically, and nearly half of the country’s banks had failed, with dire consequences for the poor and the wealthy across urban and rural communities.

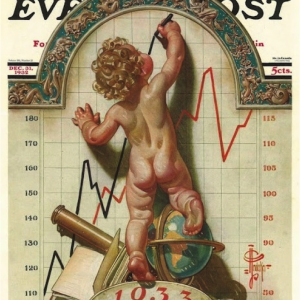

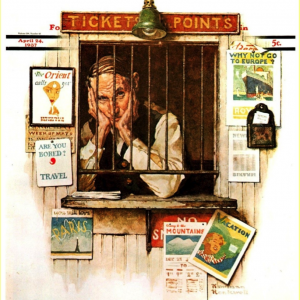

The photographs of the Farm Security Administration establish a gripping pictorial record of life at the time. Headed by Roy E. Stryker, this government agency employed such noted photographers as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, and Arthur Rothstein, among others. Among the most compelling images are those created from 1937 to 1942 focusing on the lives of southern sharecroppers, and on migratory agricultural workers in the Midwest and western United States. As the scope of the project expanded, photographers began recording “the American way of life” more broadly, as well as mobilization efforts for World War II. During the Depression, Illustrators and cartoonists found ways to provide lighthearted reflections on difficult times, using pathos and humor to express our common humanity.

Photo credits:

Florence Owens Thompson, Dorothea Lange. 1936. Collection of the Library of Congress

Bread Line, Arthur Rothstein. Collection of the Library of Congress

Evicted Sharecroppers, Arthur Rothstein. Collection of the Library of Congress

Rosie the Riveter and Women in the Work Force

Rosie the Riveter emerged as an emblem of the working woman during World War II, the center of a campaign aimed at recruiting female workers for defense industries.

Visualized in the early 1940s by American illustrators J. Howard Miller and Norman Rockwell, Rosie represented women who entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers during the war as widespread male enlistment greatly diminished the industrial labor force. In 1943, when Rockwell painted his overall-clad icon, more than 310,000 women were employed in the U.S. aircraft industry alone, making up sixty-five percent of its total workforce compared to just one percent in the pre-war years. As a popular song by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb recounted:

All the day long whether rain or shine

She’s a part of the assembly line

She’s making history,

working for victory

Rosie the Riveter

By 1945, nearly one out of every four married women worked outside the home. Gains were transitory for many, however, as female workers were demobilized to make way for returning servicemen after the war. In later years, Rosie the Riveter came to symbolize women’s rights and feminist causes.

Photo credits:

Rosies waiting to punch the clock, c. 1940’s. © The Boeing Company Corporate Archive

Rosie riveting a fuselage, c. 1940’s. © The Boeing Company Corporate Archive

Rosie installing a wheel, c. 1940’s. © The Boeing Company Corporate Archive

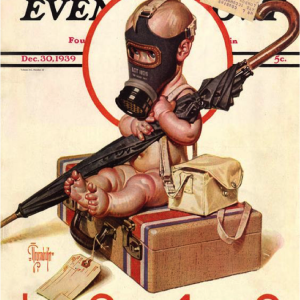

Illustration and the American Magazine

In the first half of the twentieth century, general-interest magazines like the Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s, and popular women’s magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and McCall’s, had built vast, loyal followings.

Emerging from a long period of political and economic transformation following the Great Depression and World War II Americans began to re-imagine themselves and the new lives that they hoped to lead. Production, finely tuned by wartime necessity, enabled a booming peacetime economy with a plethora of new products and modern, time-saving conveniences.

Directly linked to commerce and to selling the notion of affluence for everyone, richly illustrated magazines featured aspirational images depicting ideal standards of living, reflecting and shaping visual culture, public perception, and consumption. Top publications boasted subscriptions of two to nine million in the 1940s and 1950s, and copies were shared among family and friends, bringing readership even higher. J.C. Leyendecker, Norman Rockwell, Al Parker, and other popular illustrators working at the time were far more than picture makers—they had a crucial role in affecting cultural beliefs and desires. Their influence in shaping the American character as we know it is linked to the development of an industry that embraced the aspirations of a nation and created the American dream.

Image credits:

Baby New Year Charting 1933, J.C. Leyendecker. 1932. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.

Ticket Agent, Norman Rockwell. 1938. c. 1940’s. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.

Gas Mask 1940, J.C. Leyendecker. 1939. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.